No Way Out

No Way Out: The #1 Podcast on John Boyd’s OODA Loop, The Flow System, and Navigating UncertaintySponsored by AGLX — a global network powering adaptive leadership, enterprise agility, and resilient teams in complex, high-stakes environments.Home to the deepest explorations of Colonel John R. Boyd’s OODA Loop (Observe–Orient–Decide–Act), Destruction and Creation, Patterns of Conflict — and the official voice of The Flow System, the modern evolution of Boyd’s ideas into complex adaptive systems, team-of-teams design, and achieving unbreakable flow.

140+ episodes | New episodes weekly We show how Boyd’s work, The Flow System, and AGLX’s real-world experience enable leaders, startups, militaries, and organizations to out-think, out-adapt, and out-maneuver in today’s chaotic VUCA world — from business strategy and cybersecurity to agile leadership, trading, sports, safety, mental health, and personal decision-making.Subscribe now for the clearest OODA Loop explanations, John Boyd breakdowns, and practical tools for navigating uncertainty available anywhere in 2025.

The Whirl of Reorientation (Substack): https://thewhirlofreorientation.substack.com The Flow System: https://www.theflowsystem.com AGLX Global Network: https://www.aglx.com

#OODALoop #JohnBoyd #TheFlowSystem #Flow #NavigatingUncertainty #AdaptiveLeadership #VUCA

No Way Out

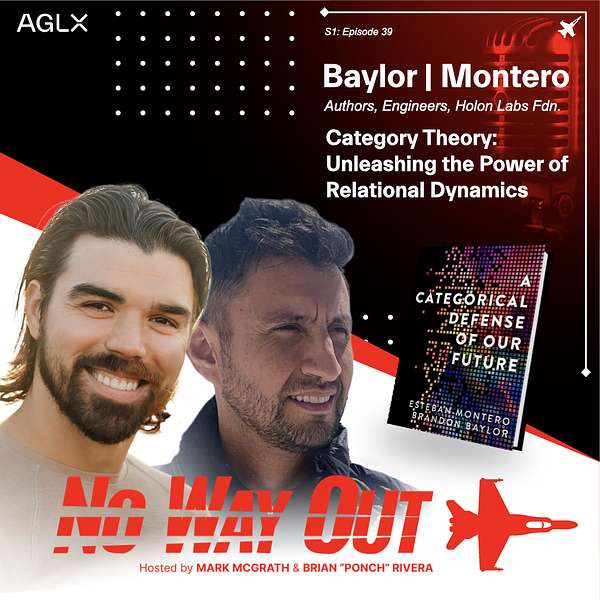

Category Theory: Unleashing the Power of Relational Dynamics with E. Montero and B. Baylor | Ep 39

What is Category Theory and what are its connections to complexity-based safety?

Join authors Esteban Montero and Brandon Baylor as they pair up to unpack the complexities of modern system theories, articulating the significance of embracing change and courageously combating complexities. The conversation ventures into the practical dynamics of digital technology, underscoring the challenges of interoperability and scalability.

As the discussion deepens, they explore the inextricable bond between safety and system components and engage in an intellectual discourse on the role of relationship analysis within systems. Pooling their knowledge, they journey through the challenges of dealing with infinite safety possibilities with finite resources and illuminate the role of the System Theoretic Accident Model and Processes (STAMP) in accident causality.

Diving into the world of data, they touch on the importance of context preservation, examining the concept of data as "a constellation of sets, schemas, and interpretations". The episode then takes a futuristic turn, introducing discussions about the potential of embedding data within DNA structures or biological systems. They also draw from the concept of 'Active Inference' to broaden the narrative around perception and category theory, which allow for a more nuanced and comprehensive accounting system for sense-making.

This episode encourages listeners to face complexity with courage, rethink current methods, and opens a world of possibilities around data and technology, making it a must-listen for anyone interested in understanding complex systems better. Whether you're a data scientist, a student of philosophy, or simply a curious mind, this is the podcast episode for you.

Full Episode on YouTub

John R. Boyd's Conceptual Spiral was originally titled No Way Out. In his own words:

“There is no way out unless we can eliminate the features just cited. Since we don’t know how to do this, we must continue the whirl of reorientation…”

March 25, 2025

Find us on X. @NoWayOutcast

Substack: The Whirl of ReOrientation

Want to develop your organization’s capacity for free and independent action (Organic Success)? Learn more and follow us at:

https://www.aglx.com/

https://www.youtube.com/@AGLXConsulting

https://www.linkedin.com/company/aglx-consulting-llc/

https://www.linkedin.com/in/briandrivera

https://www.linkedin.com/in/markjmcgrath1

https://www.linkedin.com/in/stevemccrone

Stay in the Loop. Don't have time to listen to the podcast? Want to make some snowmobiles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive deeper insights on current and past episodes.

Recent podcasts where you’ll also find Mark and Ponch:

Welcome, brandon Baylor. Esteban Montero, just real quick. Would you mind a quick introduction? We'll start with Esteban, thank, you, pons, for the invitation.

Esteban Montero:Very honored to be here. So I'm Esteban Montero. I was born in Chile and I started my career in the copper mining industry in Chile, in the Atacama Desert. So that's where my relationship to science and engineering and improvement and all of the relationship to the world came about, because mining is a really interrelated field with the natural environment in Chile and with the society and with the economics of Latin America. So that's where I got hooked in and then I quit my job, I decided to learn more, came to the US to study and that's where I met Brandon at Chevron.

Brian Rivera:All right, brandon.

Brandon Baylor:Yeah, no, thank you, pons, for this awesome opportunity. Really excited to be here talking with you guys this morning. So, similar to Esteban, my background is in engineering, so I've been working in the energy field for my whole career about 12 years now, and that's a. I think we all can tell that the energy system is getting more complex, more diversified, more things that need to come together to sort of lead us into the future. And so, as an engineer, dealing with that complexity throughout my whole career, trying to find ways to go about it and integrate these different systems, integrate our perspectives so that we can have better outcomes in terms of safety and performance and so on. And, yeah, similar to Esteban, I had a fortunate opportunity to go and study and sort of get a formal training in sort of systems thinking, systems theory, and that's really what brought us together to try and tackle this together.

Brian Rivera:Great, and we'll talk about how we connected here in a little bit with Brandon and how I met Esteban. But before we do that, our podcast is named no Way Out and I think you have a comment on that. You want to take that, brandon?

Brandon Baylor:Yeah, no thanks. We love the name no Way Out. We actually, in the opening sort of chapter in our book, we talk about similarly. This idea that there is no way out of complexity is how we phrase it. And we do have a saying in the book and amongst ourselves that we say, just to put a spin on it, we say there is a way out and the way out is through. And so, you know, let's discern what we mean there. So you know, we agree, complexity is inescapable.

Brandon Baylor:I think that's sort of the thesis of the podcast and we love that. No matter where we turn, we're faced with this realization that there is no ground to stand on right when dealing with complex systems, and we think that we're missing a way to sort of pierce through what we think is holding us back and a lot of that, you know. The way out is through means. How do we overcome the fear and the shame that stops us? What are the incentives and structural reasons for us to not have the courage to accept that there is no way out? And then, from that sort of place where we can relax with the situation and, you know, from a place of humility and curiosity, start thinking about these ideas of how to bring math and science and art and all these things to sort of open up possibilities for the future. So I just wanted to put a nod to the podcast title and give it our personal interpretation, because we love that.

Brian Rivera:That's great, I appreciate that, and Island's a disconnected effort. You refer to that in the book and I don't think he uses the exact phrasing there. But the idea of destruction and creation we have to go through these cycles, we have to shift these paradigms and that's what we're going to really do today is kind of shatter that. And we're going to talk about category theory perhaps and category theory has popped up in my feeds and actually on the podcast a couple of times from the folks that are looking at active inference, you know how, which leads to consciousness and perception and artificial intelligence, and it has so many connections there. Can you share with our audience why this topic, which they may know nothing about, is so important to them and maybe some examples of how are you using it right now?

Esteban Montero:Well, I mean connecting it with the way in how you answered the question of the way out we realized that in our path out, in our response to fear and shame, we have a lot of the reasons why we create problems.

Esteban Montero:Actually we create challenges and disruptions for systems and for society and for our industries. So it is in the practice of staying a little bit longer in the discomfort of what you would describe as Bucca, as the complexity, as the inescapable challenge of like not really understanding what's going on. If you stay a little bit longer there and kind of embrace that feeling of discomfort, you can not necessarily find immediately the answer, but you can avoid certainly running into more problems, creating more problems for yourself and for the industry and for the companies and for the products that you develop. So I think that the book in a sense is an invitation to hold it for a little bit longer, if that makes any sense, and in that there is a lot of practice to be done. We are trained to kind of reject discomfort and to run into answers and to have a very utilitarian way of thinking about problem solving. So that's why the book is an invitation for us. We call it the defense because it's such a problem, it's so persistent in our personal lives and in our professional lives.

Brian Rivera:So getting comfortable with being uncomfortable, staying in that liminal space, if you will, is so critical in dealing with the challenges that are all around us. And I like the something you brought up. Sometimes the challenges we make or the problems we make are self-induced. You know, in fighter aviation we had something known as pilot-induced oscillation. You can create your own problems by compounding them, by reacting to the environment when you should just put your. We say, sit on your hands, Just kind of relax and see what the environment gives you first. So a lot of amazing connections there. All right. So the book it's a categorical defense of our future. That's the name of the book. Again, it was published in the last. When did it come out, by the way? Because the last note I had was from June 22. October.

Brandon Baylor:October Okay.

Brian Rivera:So I was the end of the book not too long ago and, like I said, I gave it to my wife first to kind of chew through it. But let's go through a little connection here on how Brandon and I met and how I met Esteban. So, through the Kinevan network, complex adaptive systems, I met Brandon through Gary Wong and Gary said hey, you need to meet up with this person Going through MIT at the moment studying stamp and we'll talk about that here in a second and studying with the, is it Nancy Levenson? Is that correct? So there's a safety aspect we're going to start off with, and I think this is pretty unique, because how does safety relate to data sciences, which I believe we'll be talking about here shortly? So so, brandon and Esteban, when you were at MIT, were you there to learn about category theory or more about safety, or what's the relationship between safety and category theory?

Brandon Baylor:Yeah, I can. I can describe my journey there. So, yeah, the program that I attended in for my master's degree was all about systems design and management, right, so that systems theoretic foundation and I was really taken by the classes around system safety. And, you know, at first I was thinking I have a decade of experience with a, with a, you know, a global organization dealing with safety with a great track record, and so what, what is there to learn? What you know, sort of thing. But I sort of practice my beginner's mindset and went in and went in and was really just taken aback by the paradigm shift around safety and thinking of it as not like a failure problem but a problem of control. How do we deal with context? How do you keep humans in the loop? How do you, you know, control and put constraints on the components and the system to sort of make sure the emergent outcome that you want, like safety or security, is sort of achieved. And so that just really took me down a path of understanding that the relationships between how components are interacting is more important than perhaps defining the objects themselves, and so that that's like a core premise of systems thinking. Right, and I think it's almost cliche at this point. Everything is connected. I think we all know that, especially in our community, talking about complexity. So it was good to get that theory around, systems thinking as a concept.

Brandon Baylor:But what I found is that when you go and try to apply these modeling techniques system modeling, model based system engineering you know it's very hard to scale and actually implement any of the models and the technologies. And how do you get them to interoperate Right? So this is sort of the new phenomenon in our last 20 years. With digital technology, internet of Things, cyber, physical systems, there's, like this, increased need for interoperability and to do it at scale.

Brandon Baylor:And because there's a proliferation of like data formats and structures and schemas and viewpoints, the current approach that we take to deal with that is sort of very based on standardization or, you know, a universal data model. And so we we found inspiration through a mathematician, a leading category theorist named David Speedack, who put this analogy out there. That really has marked our journey. He calls it the Copernican Revolution, like, first we thought the Earth was the center of the universe, then we thought the Sun was the center of the universe. Now we realize there's no need for a center. You know whether that's a data model or like forcing us to have one perspective. It's a constellation of data sets and schemas and interpretations that have to come together to create the whole, and that was a big shift for us and led us into this sort of world of mathematics that can represent those things.

Brian Rivera:Okay, in your book. I want to touch back on safety just to make a hopefully make another connection here Reason Swiss cheese we use it quite a bit. We also use five Y's quite a bit and there's a lot of danger in using them in complex systems. For those of you who are not familiar with reason Swiss cheese model, it's been around for years. We use it in fighter aviation, we use it in military. It's a way to kind of see, hey, when the holes of the Swiss cheese lineup, you have an incident or an accident or you can actually have something that's favorable that happens to you.

Brian Rivera:It's a good way to explain things. It's not universal, right, it just doesn't work everywhere and that's not how the universe works. So, being stuck with these models in our heads, they could be pseudoscience or they could have some type of context dependent use which we tend to find things in hey, this is contextual, it works here and maybe not over here. I think the same thing is true with some of the data capabilities and again, I'm not a data expert. Just listening for my wife talking about the relationship between data, she would say, hey, this has relationship between this and that and that's how you connect things, and that's what we do with human systems sometimes as well. We'd say here's a relationship between X and Y and here's a relationship model or relational model between two objects.

Brian Rivera:But my point behind this is we have to shift the way we think. You know, go through that cycle of destruction and creation, destroy our old way of thinking to come up with something new. And it's not to say all those things that we had in the past are useless. They're still useful in context, correct? So you know where we're going with the new data structures and maybe the semantic web, I think it is. There's still value in having the old paradigms. You don't throw them out. They're useful in context, but they're not going to be, may not be, as useful in the future, just like reasons with cheese cannot be used everywhere, right? So I don't know if that resonated with the two of you. Can you expand on that or maybe dampen some of the comments I shared with you?

Esteban Montero:We cannot add something, I think. So what you're describing when you talk about the old paradigms and the mental models is kind of the story of what is happening in safety. We have a very solid decade-long history of success I would call it in managing safety in many different industries. In aviation especially, like in defense, these guys are amazing. It's a miracle how they keep it together and they have methods that are really the result of many, many years of experimentation and development, and so it's really hard to criticize and to come and say, well, what else can we do? What can we do different when we have methods that work. I mean, in this moment as we speak, so many airplanes in the air successfully flying right, and so that's, I would say, the first challenge is like the walking the line between saying how do you recognize what is good about this method, at the same time that embrace the gap and understand what has to be done to kind of address what is missing. And so I can point to a couple of things that are missing. One is when you ask the question what can go wrong or what can happen that harms us or that makes create problem for us, the answer is infinite. So that's useless, right, and so how do we get to navigate a space of infinite possibilities in a way that is useful? We have limited resources and limited amount of time. How do we use those resources in a space that is infinite? So what we do in the current methods is to use experience, is to use experts, and these experts, guided by facilitation tools I would call them you can describe them as analytical methods but they are really guides, pointers that they use. But it's really relying on these experts to use previous experience and to use perspective, that they have to come up with things that can go wrong. Now, in complex systems, in the systems that we are starting to see more and more right now. That is not enough, because so many other things can occur. So what happens is that we start trying to use analytical methods. Now, this is the challenge no matter what you try to do, there are still infinite possibilities of things that can go wrong. So there is no way to overcome that problem. Again, there is no way out. There is no way out of the issue that there are infinite things that can happen to an airplane that is in the air. And so how do we navigate that infinite space? Again analytically, and I think that's where contributions like Nancy Leveson are so relevant, because she creates a systematic way to go step by step. You don't need experience Actually, experience can harm you in going through the process of STPA.

Esteban Montero:Of Nancy Leveson's view, you just have to follow the systematic approach that she came up with and you can come up with the answer to what can go wrong. Now the issue is, in her own words STPA it's too good for its own good, and what she means by that is if you go to a manager of an airline and you say, look, these are the 900 things that can go wrong that you never thought about and, by the way, I actually have done that. I went to a shipping company once, did an STPA on a process that was the most secure safety process in the company For decades. They have not identified one new thing and without any experience, just following the steps, we identify 800 new things. The manager didn't like it.

Esteban Montero:You will think that somebody in charge of that process will love that answer. Right, somebody will say well, that is great news, you found 800 things that are going to be useful for me. Well, it's terrifying, that's again, that's a scary place. And so that's where category theory, I think, can come in. It can help us navigate that space of how you analyze systematically, something like using a more rigorous method, but I have to say it still doesn't resolve the issue of you will come up with 900 things, and then what do you do with that? And so that's why I think it's so hard to answer your question of how do we break the old paradigm. Well, the old paradigm is very successful, so we don't really have to break it. We have to add stuff on top of it and change by evolving into something better, but preserving what is good about it, which is the heuristics of people, how people actually make use of experience and perspective in a way that is useful at the end of the day.

Brian Rivera:Esteban, I want to potentially touch on something you brought up here about the I'm going to call them patterns right now, but the possible ways things can go wrong. I'll do that first and then after that or before that, could you either of you comment on what is STPA and or stamp? So I'm going to go ahead and try this real fast. When you go into an organization, people will say, hey, if there's four people or four nodes, how many links between them? And there's a simple formula out there, that's what is it? N times n minus one over two, and that gives you six. So four nodes gives you six links and I believe I'll just look it over the patterns in that within those four nodes is about 64. That changes when you go up to 10 nodes. So 10 nodes you get, I believe, 45 different links, 45 different communication pathways.

Brian Rivera:All right, but here's the shocker the number of patterns in that are 35 trillion. So I think, just to kind of frame I think that might help frame people understand when we talk about how things can go wrong when you start adding more components to something. It's not a linear thing, or I think that's what. Yeah, it's not a linear thing, that's a linear equation. I believe it's worse than that. 35 trillion is a lot of patterns, which is 10 people, but that's not how everybody frames it right now. They frame it as look at those 45 links. Does that resonate with you on what you're talking about, when we have to think differently about these potential problems? Yeah, absolutely.

Esteban Montero:Okay, so, absolutely so. What you are describing is the combinatorial aspect, let's say the amount of combinations or permutation of things that can create new types or possible scenarios. I would say that there's another factor, which is the fact that systems are really open and not closed. So what I mean by that is that you can say that your system has six nodes or six components and pretend that that's it right and say what can go wrong over my six components? But in reality, the more systems become interconnected and complex, the more the boundary of what is defined as the system, the more your capability to say it's only six, what defines my system is only the six things and nothing else, becomes obsolete because suddenly something else can come and interact with your system in a way that changes it, and so the openness of the system is another aspect. So, even if it was not true what you said and there were only two nodes and the amount of combinations was very small, even if that was true, there are still infinite ways in how that those two nodes can interact with other things that you don't even know that they can interact, because your system is truly open.

Esteban Montero:Now, this is a debate on systems thinking and engineering on, like our systems, open, or can we really define boundaries right? What is an airplane? Is the, is the? Does the airplane include other things that are around it? And so that's a debate, but I think what we believe is that that is a. The definition of a boundaries is an arbitrary thing, and we can, and when we let it go, we see how it's infinite and complex in a way that that can help us go into new directions of thinking.

Brian Rivera:All right, and the shift from behaviorism inside of safety and things like that, what we you know reasons with cheese and what we had in the military human factors accident classification system, I believe kind of reductionist approaches. I would put them more towards that end. So, stamp and STPA I believe I'm saying that correctly. Can you just give us a quick overview on what that is so our listeners can understand what we were just talking about?

Brandon Baylor:Yeah, happy to take that one Right. So so in the, in the, in the Swiss cheese model, like, it's based on a, on a framework that's called the linear chain of events, basically like if you just keep the dominoes from tipping and creating this compounding effect, then you're good. So it really leads us to put in barriers in place and sort of redundancy and focus on failure as the main mode of sort of breaking the chain of events. It's a very linear and reductionist in that way. And so stamp stands for system theoretic accident model and processes. So it's like a new systems theoretic framework to base our accident causality model on.

Brandon Baylor:Rather than being a linear chain of events, you know, it's looking at the dynamic context, dependent interactions between system components that lead to safety as an emergent property, as you guys were describing. And so, whereas stamp is the foundation on how to sort of view systems as as control theory kind of loops of feedback, like how we update our belief system, how we go about interacting in a dynamic way, stpa is the specific process analysis, system theoretic process analysis that guides you step by step, as Esteban was saying, through a scenario in a control structure to understand at all levels, to go into the person turn in the wrench? What are the interactions and controls in place to sort of create that dynamic emergent behavior? Okay, and so.

Brandon Baylor:I just wanted to Sorry, yeah, go ahead.

Esteban Montero:No, no, no, to finish that.

Brandon Baylor:Yeah, I just wanted to kind of tie it back to your point, esteban, and what Pont was saying, like because he was talking about the combinatorics and that's the reason why we struggle.

Brandon Baylor:And I just want to say, to try to tie it back to category theory, that you know we're dealing now with large scale networks of relationships, because the model is relationships between entities and components, and these are people, these are the software. Like it's, it's not a, you know, it's not predictable, like you can't predict the behavior of how collective decision making kind of comes about in that uncertain and ambiguous environment. And so even even like graph theory, which is the branch of math that models networks, is unable to describe the richness and the meaning and the structures right that are going on and those scale like scenarios. And so we need to like we've been using category theory to extend graph theory to encode behavior In those networks and reason about the structures without getting distracted by the data or the details. You know it's it's allowing us to just reason very precisely about how things are related to one another, and that's sort of the premise.

Brian Rivera:Wow, we could. We could branch off in about 20 different directions on this right now.

Brian Rivera:I'm going to try to keep us on a on a okay pathway that lines back to your book and on the topic here. So leaders are challenged by this new way of thinking. You know, not necessarily systems thinking or complex adaptive systems thinking, but this new way of thinking about data integration or relationships within data. In your book, you bring up six scams and you also talk about seven features. You know this podcast and predicated on the features of the world that we just can't avoid. We have to go around them or we have to work through them, just like you pointed out earlier. So what's the limiting? What's preventing leaders and organizations from embracing this? You know, whether it be stamp or this new way of thinking about complex adaptive systems or even category theory, what's, what are those things that prevent them from really starting to embrace it?

Esteban Montero:Yeah, I can start out one I. I mean one of our, our feature, one of our things that we describe in the book is definitely fear and shame. I think we are If we look at our own careers. I mean and I'm speaking for myself, because when I was little, the question of what am I going to become, what am I going to do, is a is a very pressing issue in society, like what am I going to do with my life? How am I going to be productive to the society? And and and. So we, we have that tension and that fear and we hold into something a discipline. I'm going to become an expert engineer or an expert pilot or an expert, and I think that to be known for mathematics or computer science, it's these disciplines and these ideas of kind of we call them buoys, like it's like a thing that we hold in the middle of that kind of storm and and and.

Esteban Montero:So what is what is a little bit tragic, which I think is that society rewards us for that, and so a lot of, a lot of our leaders and a lot of our executives, a lot of the people that are in power of decision making, are people who have been successful in building those let's call them armors of societal clues that tells them that they are good for society, like they became good mathematicians or they became good pilots and so on.

Esteban Montero:Right, and they became so good at it that that society rewarded them. So so I think, after many, many years of of of hiding the fact that we are really afraid, that we really that we are really scared of just being and so that's been, of being rewarded as the most, as the best, as the fastest, as whatever, we are asked by people to talk in an unconstrained way, to say what about if we just look at this thing and we can think about it in an open-minded, beginner's mind way? And that is a really scared thought, it's a really primal question. That brings us back to high school what are you going to do with your life? And nothing is not an answer. So you have to have an answer, and so I think that's one. I don't know, brandon, if you want to throw another one.

Brian Rivera:While you're thinking about that. I'm still trying to forget what to do with my life, and I'm not in high school anymore.

Brandon Baylor:Well, and I just want to do it.

Brandon Baylor:I mean Ponce kind of hinted at it and you articulate Esteban, it's that pattern of destruction and creation of the self. Really I think what Esteban was saying ties back to that point you made. Ponce of my experience with this journey was basically questioning so many assumptions and conditioning that I had been living through my entire career and in my personal life. And it's a tough personal journey to say maybe there's a different way and I need to unwind all these sort of vexed preconceptions that I have about how the world works and how things are interacting. And so that makes a lot of personal discipline, I guess, to take that journey and I don't call it an evolution, which is always like an extension, a rolling out word of things. It's like an involution, it's like an inward journey of destruction and creation, sort of challenging and reflecting, contemplating things, because that's how we found that study, the self, and you can sort of orthotherm to that, so you've got to have something to do with it.

Brian Rivera:Yeah. So one of the things you brought up Shaymin fear in the book and Esteban talked about it is ego. Ego is in there too, and one of the things the default mode of operation in an organization or the default mode network in our brain. We have to push that down, that ego, that self, so we can have access to higher entropic states where more novelty is and we can see more connections. And I'm going to look behind me real fast because I wrote something on the board.

Brian Rivera:I want to make sure I get this right. We've got to find those points of intersection right and you had that in your book. That's what we have to do and that's that cycle of destruction and creation. So, with that being said, you have the seven features, you have the six scams. Let's dive a little more into why. What are you doing with category theory and why is it important to leaders? Right now we really haven't hit on this, so we kind of led up to it. Let's go ahead and show everybody what it is we're talking about. So why is this important and what is it?

Brandon Baylor:Yeah, so I won't formally define it, but basically it's a branch of abstract math and the reason, you know, we found such a connection to category theory as a language to describe relationships is that it is kind of another, better name for it perhaps is called relationship theory or structure theory. It's the study of relationships and transformations of networks and how things compose or sort of come together to understand the whole right, and I derive the meaning of the whole from the constituent parts. That's really what our theory is all about, and the mathematicians use it to transport ideas from different branches of math to help them solve theorems. Basically, it's like a meta language that lets you do math on math, which sounds kind of weird, but that's the idea is that it lets you translate between domains in a way that has a common language, a common abstraction. You can wrap things in to get them to relate to one another. I mean, my brain just thinks systems, right and like.

Brandon Baylor:When I hear that idea of like, how do I you know the three of us have different mental models and schemas in this, in this conversation, like you know, are we called? You know how do we define, how do we figure out meaning amongst the three of us Like I call an object blue, you call it pink, s1 calls it green. But what if we mean the same thing and the labels are what holding us back from actually having a productive conversation? And so category theory says we'll drop the labels. Who cares? You know what the label is. Just understand how my context and interpretation relates to your context interpretation and let's think very rigorously about how to transport my schema into your scheme and so that when I say blue, you hear pink, like it's that, it's that I. It's a language that's very precise and rigorous to let us transport ideas and recontextualize things in a way that's sort of very precise.

Brian Rivera:So that's yeah, so I want to. So my conversations with data scientists or my wife's data curation, this is what I understand and help me. And you know, we got to talk to folks that are listening to this podcast that are like what are you talking about? So linked open data, the relationship between different, disparate data sources is predicated on certain words. In those relationships, that requires humans to go in and put context or meaning to that data, even though they may or may not have an understanding of the context itself. There's a danger with that and there's a danger with just kind of leaving the data the way it is, kind of, you know, in an unstructured way.

Brian Rivera:In complex adaptive systems, we rely heavily on interactions and that's the relationships that are more important than the quality of the agents. That's what we say, right? When we build a high performing team, it's not about the quality of the individual agents, it's about the quality of the interactions. So we want to increase the quality of those interactions or those relationships, and that builds an emergent property of a higher performing team. So I believe that's the same thing you're trying to do with data, right? That's the approach, without using any math, is we're just saying, hey, we want to work on those relationships and leave that context there with the make sure it's context rich.

Brian Rivera:And you also point out something that I think is critical, and this has to connect back to art. Art shows us the way because art has context and you talk a lot about context. So we're coaching organizations. We talk about context as well. Context matters a lot and matters. It's probably one of the most important things, because that will determine so much about what you do next. It's not the other way around. So, esteban and Brandon, can you help me build on that and make that connection stronger to gategory theory and what you're trying to do with the data?

Esteban Montero:Yeah, maybe I can take that one, I think complementing what Brandon said. I mean, pont, you just hit something really important that is so subtle and we struggle with Brandon saying this, so let's try to uncover it for people listening here. So we are trained to think in problems, in projects. Think about the definition of a project. It's something with a beginning and an end. A problem has a solution, and so we are not trained to think about how problems relate to other problems. That's kind of a meta problem for us. So people in academia think about that, but in industry, we have a problem and we solve it. We have a project and we finish it, and so the way in how we think about the relationship of problems with other problems and solutions with our solutions is you can call it systems thinking, but it's a science that is kind of a little neglected. We found one good engineer one time in our journey who has tried, very successfully, category theory, and we asked him like why are you not using it even more? And he said, well, there's no problem that I cannot solve without using category theory. So any problem I can solve without category theory, so why do I need it? And so that's why it trips us.

Esteban Montero:It's the idea that like and so I guess I want to answer your question kind of saying which role in society or in a company or in an organization or in a team is thinking about how to connect problems with it all. There is a team working in problems type I, like maintenance. There is another team working in problems type B, marketing. There's another team working and so but who is thinking in the, in how you connect them together? And so usually it's the management team. But the management team doesn't do it from a very science based perspective. It's very organized, behavioral. There's a lot of you call it pseudoscience. That's a good word. I think I agree with you. There's a lot of pseudoscience around how to do that. A lot of management school is based on a lot of pseudoscience. So category theory, I think, is exciting because it brings science to that problem, real science, real math to that problem.

Esteban Montero:And I think art and other fields do not think that way. They don't start by the premise of like, oh, I am painting and painting, that's what I'm doing. I don't think they. I think they break constraints and boundaries between disciplines from the get, go from the beginning. Next week I'm presenting in Spain in a conference called interdisciplinary school, and one of my points is why don't we call it non-disciplinary With that? We use that term in the book as well, and the moment that you call it interdisciplinary, you start with the assumption that you have to have a discipline to start to be part of that process. In order to be interdisciplinary, you have to have a discipline. If we think about it from a non-disciplinary point of view, then everyone is invited and every idea is invited and every framework is invited, and then it feels a little chaotic at the beginning. But that's when category theory can help us reason about that chaos and about that complexity in a way that I think is exciting because it hasn't been addressed until today.

Brian Rivera:Okay, and that conference when I took a look at it, it looks like a journey of what John Boyd went on was just looking at all these different disciplines, right, and then going back to your point there. But it's bringing you know, finding the connections, the overlap, the intersections, the relationships between them, and that's you know how, basically, he came up with the Oodaloop, and that's the power of these things. Is he called it creating snowmobiles, right? You want to go out there and start connecting disparate ideas and I think that's essential in what many organizations are trying to sort out. When it comes to big data, I'll call it big data for now. So this is like I said earlier. There's so many directions we can go on this. But back to the topic of, you know, complex adaptive systems, interactions and going back to why leaders need to be paying attention to this. What is the desired outcome by using this type of thinking on and it could be data or whatever you want to pick on guys, but maybe just data or information.

Esteban Montero:Yeah.

Brandon Baylor:No, I wanted to address this directly because you asked about the data modeling and that aspect, and that's really the sort of the first true application of category theory and industry that we've seen is sort of like we call it categorical data migration or categorical data integration, and you said it very well, paunch, that the challenge is that if I need to think about a complex problem as a decision maker or a leader, I have to kind of pull data models and different representations from a disparate set of, you know, teams and sort of data models, right, and you know, today we have humans sort of dealing with these systems of tables that are like objects that we have to reason about data sets, and a human has to sort of chase the transformations of how data gets from table A to table B to table C, right, so, like a human has to carry the context in the meaning of like, when I trace all these different connections in an information system and that's error prone, right, it's time consuming, it's like no human has the capacity to deal with that, right, their intuition can't handle it. Because if you've ever done any data modeling, it's like a spaghetti diagram of just relationships and joins and all these complex database stuff. And so what category theory does? It says okay, you know, if I know that table A is connected to table B and I know that table B is connected to table C, because I'm using a sort of a mathematical formal system, I can deduce through inference that table A is connected to table C and that leap is called composition. It's the composition of these two tiny arrows to get the big one. And now I don't have to carry that knowledge around in my head anymore.

Brandon Baylor:As a data modeler, I can let the system keep track and make sense of this relationship that I just established between these three tables. And just imagine, as we said, combinatorically, if I can make those inferences to these sort of indirect things that aren't directly connected. But I know that there's an indirect connection through composition, you know, and I in the math sort of gives you abilities to detect like, oh, you create a contradiction, this path doesn't equate to this path anymore, and it'll give you feedback to say, hey, there's an inconsistency here, whereas today a human has to carry all that extra baggage around mentally and it's almost impossible to keep track of. So it helps us improve the data integrity constraints that need to fly around to deal with all this heterogeneity and, to your point, that leads to higher quality decision making. Because now I can trust that I'm not creating a contradiction when I put these two things together.

Brian Rivera:Okay, machine learning and AI. You mentioned something in your book about explainable AI. It may not exist, right? Could I get your take on that guys? Just what your view is on explainable AI using category three?

Brandon Baylor:Well, let me build on my last point because it's very related, right. Like data is, you know, the raw ingredient that we think of to sort of do a lot of these machine learning problems, right, and the data science activities. If I can just train this big data set on things we already know how to do, then I can sort of get a statistical prediction. And so the difference between that sort of paradigm of machine learning, which is statistics based and actually never gets us to the 100% certainty, because that's the nature of how it works, what we've seen in sort of category theoretic approaches to sort of machine learning, is that it's not reasoning about a big set of data, it's reasoning about the structure of how things are related. Like again, like, forget the data for a second and just look at how these data columns are related and I can encode constraints at that level, because now I'm at this higher level of abstraction, I don't, you know, and that can give me a more certain sort of symbolic way to reason about how things are connected versus a statistical likelihood of, you know, prediction. So that's the difference between, like safety and safety situations.

Brandon Baylor:I need to meet all the requirements 100% of the time. I need to. You know, I want to. You know, when I put my hand in the combined space and rotating equipment, I want to know for sure that something isn't going to happen. And so I worry that. You know we use machine learning based on statistical. You know it's never going to be 100% and sort of that. 1% isn't enough. We need new ways to sort of insured integrity of systems as they come together, and that's where category theory shines.

Brian Rivera:Okay, how about this? Is there a connection to, like self-driving cars and the use of category theory? Is there a way to make a connection there?

Esteban Montero:Well, I would say that the challenge, so the paradigm between the paradigm shift, I would say between category theory and the machine learning behind kind of self-driving cars, I would say, is the idea that with enough connections you can achieve the intelligence that you require to drive a car. And basically that's an explicit statement of many of the leaders of car companies that are trying to pursue autonomous driving. It's like we just have to push this through until we get enough people trying it and at that point it would be a smart enough and it will connect. And on the other hand, so that's what I will describe as what in cognitive science is called connectivism or basal cognition, the idea that, like you, can have from the bottom up these different entities connecting to each other and achieve combination at some point. This is kind of a predominant theory right now in cognitive science and that's what it's really really popular way right now.

Esteban Montero:Thinking about that, on the other side, there is this systematic way of thinking which is kind of attached to category theory, and I think and this is just my opinion, but I think it's a mistake to think that you will describe exactly how a car should drive with no mistake. There's no way, because, again, there are infinite possibilities and so you can describe in a categorical way exactly how it will work. And so that interpretation of category theory used to drive cars, I would say, is a misleading one, in that sense there is more hope in a basal cognition of cars driving than in the other one. Now the problem remains that Brandon is pointing out, which is how do you address that 1% in where the car thinks that it should stop and it's not stopping because it misinterpreted something probabilistically right. So I think the answer is a different answer, and I think category theory has a value in that I think there is a cognition that is more embodied, multi-sensorial. I think humans are better than machines, not because we have more or less connections, but because we have different types of connections working all together at the same time. And so, if you think about it in a multi-sensorial way, if you think about it in a way that is more embodied, with the context and with the different aspects of what is going on at every part of the driving dynamics, there is an aspect of composition. If you think there is the perspective of my smell senses and there is a perspective of my vision and there is a perspective of the noises I am hearing, and there is a perspective of the geographical places in where I am and there is a perspective of the time of the day. All of those things play together. Now the problem that we have, I would say, in a technology point of view, is how do you bring those perspectives together and compose them? And that is where I personally believe the power of category theory as a translation tool, as a composition tool of multi-sensorial things is addressed.

Esteban Montero:Now, just back directly to the point that Brandon was pointing out In a deterministic world we have to decide do we stop or not, do we hire you or not, do we buy or sell? Those are deterministic answers. So I do not think that category theory or any mathematical tool will ever be able to describe the full, systematic way of arriving to this answer. I don't believe that. I think there are infinite ways to achieve that. So maybe for a specific case once, but it is useless the next time. But I do think that if we bring multiple perspectives and compose them together using a tool of translation, then we will have a complementary way of thinking about basal cognition. In a way, basal cognition requires composition, because these different elements have to come together, and in order to come together, they have to talk each other's languages, metaphorical languages. So I don't know that person. No, that is extremely helpful.

Brian Rivera:It is triggering a couple of ideas here. Number one humans, I don't think could have a true understanding of the reality, so why should machines? And then two, a recent connection I think Brandon and I talked about this actually we talked about a few months ago. Active inference is popping up in a relationship between category theory. Any comments or thoughts on how they work, and what are you guys looking at when you start looking at active inference and your work with category theory?

Brandon Baylor:Yeah, I think, just to put it, keep it pretty high level. I think when I think about the active inference model of perception and action, what I see category theory useful for is the mathematicians often refer to it as an accounting system. It lets you keep track of meaning and sense making that's happening. And multiple systems are multi-scale, they're diverse, like Esteban said just now. Multiple perspectives with their own language, their own vocabulary have to come together to form that perception so that you can then act on it. And that's why we see it as a language to represent those different things and help them come together in a way that preserves the consistency of meaning, as they all need accounted for.

Brandon Baylor:Basically, we don't have a tracking system to deal with all that meaning in a way that can lead us to more collective, better collective decisions, and so that's where I see having a language to sort of force clarity. We say clarity over simplicity because a lot of times our response to dealing with a complex environment is like let's simplify and that's obviously not going to cut it. And so what we say is what category theory? It kind of forces you to slow down and formalize what you're doing, like, take the time to get clarity and in that, yeah, you're spending extra time. Again another challenge for why business leaders may not like this right away. Like you invest up front in clarifying your thinking, your reasoning, but the payout is like it doesn't become this like N squared problem. Comminatorically it's like it sort of scales better because you, it's like, yeah. So that's sort of where I think category theory may play a role as a modeling, as a language, as a way to represent the multiple pieces that must come together for that perception to happen.

Brian Rivera:Nice. We're going to wrap this up here in a few minutes, but before we do, we're going to continue the conversation. After we do a quick wrap up here, we'll go into the YouTube's work here at a moment. Before we do that, I believe you guys started something new right In the last couple of weeks, in addition to the conferences you're being pulled into. Can you tell us a little bit about what both of you created? What's it? Is it a hold on, hold on labs? Am I getting that right? And why did you pick the word hold on, if I'm saying that correctly?

Esteban Montero:Well, I can answer that we started a research foundation, hold on labs and our objective is to achieve what we call collective computers, collective computation. And so we think that all of these questions that you're asking, all of these issues about how we think and how we deal with decision makings, are about the collective. Eventually, we are not single agents making decisions, we are families, we are teams, we are corporations, we are societies, we are countries, we are collectives of people, and the way in how we come together and how technology can help to facilitate that, we believe it's one of the key questions in the future of our species and our societies. So we are very excited to put our time and passion to develop this new technology, our collective computer.

Brandon Baylor:Brandon, if you want to add anything, yeah, I think also we're motivated by the way we relate to technology and computers today. They're really good at repetitive tasks and things that have some degree of certainty, and so we think that there's a space for something new and understanding how that collective intelligence emerges from interacting non-intelligent resources. But we actually push it in a different way, and I want to embrace awareness like collective awareness, and so maybe that's the way to lead us forward isn't through smarter or more intelligent, maybe it's more awareness, more compassion. Maybe taking the time to just pause and contemplate will help us, as you said, through the pain of the destructive part of our journeys that we have to take to be able to learn new things, be open-minded, reinvent ourselves, and so we think there's something to say about technology's role there and we want to put forward our best foot on research and development in that space.

Brian Rivera:Okay, before we go to no Way Out Extra Time, here is anything you want to share with our listeners about one how to connect with you, or anything else you want to touch on before we shift over to the Extra Time.

Esteban Montero:We have a website, categoricalfuturecom, and our book is on Amazon, so I mean, the contact information is there. The best way to give us feedback is through the reviews and to just give us feedback and interact and engage. We want to connect with others. We appreciate the time with you, ponte, because this is exactly why we are doing all of this. We believe these conversations are so necessary.

Brandon Baylor:You can also follow us on LinkedIn and you can follow the whole OnLabs page and that's where we post updates and thoughts around our vision, what we're working on, et cetera. So that's a good avenue.

Brian Rivera:That's fantastic, all right. Well, we'll invite our guests to shift over to the YouTube channel for now, and for those that are going to go ahead and disconnect here, we appreciate your listening to us and pick up the book here. It's called A Categorical Defense of Our Future Espan Montero, brandon Baylor. My quick review of it, real fast, is a lot of overlap with what we've been talking about for years. You know Allison's checkerboard or Swiss cheese model, new ways of thinking about safety, complex adaptive systems theory, the overlap with actually how we're training folks within some of the organizations you may be familiar with.

Brian Rivera:It's an exceptional book. It's a smooth read and, like I said my wife when she when I handed it to her because I was kind of scratching my head, am I going to read a book about math? No, it's not about math. It's about a lot of things we covered here today and her view, from her perspective, is this is a game changer in the field of data science, data curation and what they're trying to do to preserve context when we start looking at, you know, future things. So thanks everyone, thanks Esteban, thanks Brandon, and we'll see you next time on no Way Out. Thank you.

Podcasts we love

Check out these other fine podcasts recommended by us, not an algorithm.

The Shawn Ryan Show

Shawn Ryan

Huberman Lab

Scicomm Media

Acta Non Verba

Marcus Aurelius Anderson

No Bell

Sam Alaimo and Rob Huberty | ZeroEyes

Danica Patrick Pretty Intense Podcast

Danica Patrick

The Art of Manliness

The Art of Manliness

MAX Afterburner

Matthew 'Whiz" Buckley